In the old days of railways, the risk of collisions was a very real thing. Steam locomotives, with their boilers filled with high-pressure steam could – and did – explode if they ran into something, and even without a boiler explosion, their high mass and momentum meant that crashes were significantly more violent and forceful than a typical automobile collision.

Before the advent of modern block systems and signalling, there were several methods to reduce the chance of collisions. Lines with a lot of traffic in both directions benefited from double-tracking, allowing each track to carry traffic in a single direction, though even that carried the risk of rear-end collisions in the event of a slower or completely stopped train. What if there was a solution that prevented all collisions, whether head on or read-end?

Flash back to turn of the 20th century Coney Island. Today it is a sea-side amusement destination for New Yorkers with both classic and modern rides, including the famous 1927 Cyclone roller coaster, however back then it was even more so, with large and majestic amusement parks, such as the original Luna Park and Steeplechase Park, that showcased the latest in the technology of the era. The first working escalator, innovative (and often dangerous) amusement rides, electric lights, baby incubators, and a new type of food known as the “hot dog” were showcased for the world to see. In 1904, Dreamland opened. Built to replicate the success of Luna Park, Dreamland actually copied many of its attractions and took them to eleven. If Luna Park was lit up with 250,000 electric lights, then Dreamland was going to light itself with a million lights. If Luna Park had one Shoot the Chutes ride, Dreamland was going to have two. Apparently patent and trademark laws weren’t as much of a thing back then.

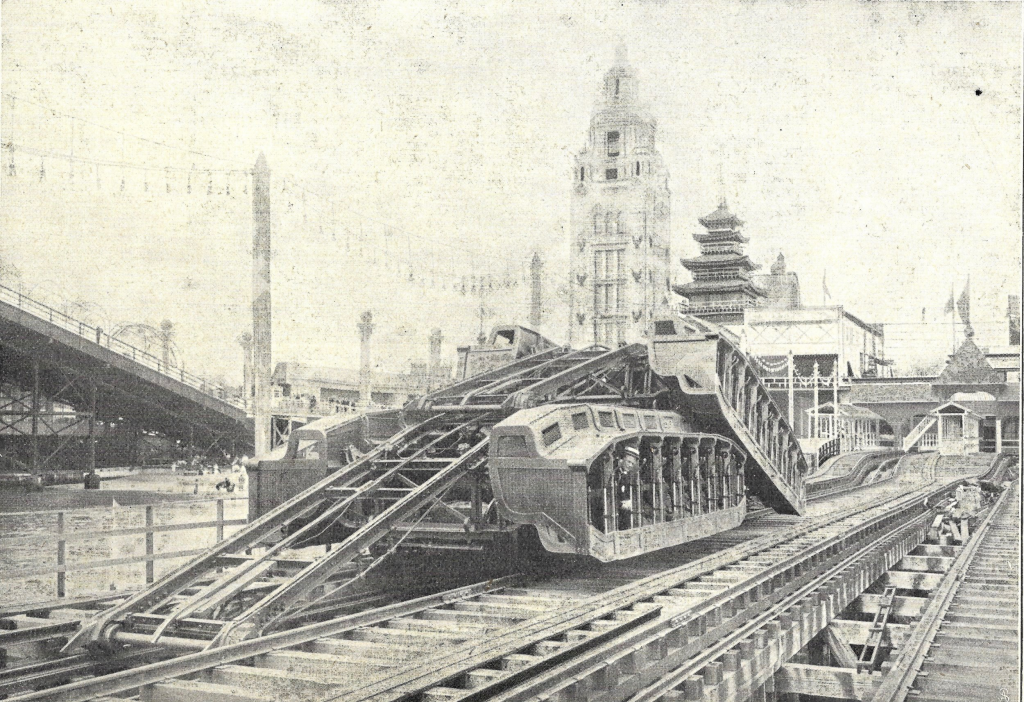

One of the novelties exhibited at Dreamland was the Leap-Frog Railway. Built on a pier stretching out into the Atlantic, this attraction consisted with a single stretch of track with two specially designed tank-like railcars that would literally go off the rails. Resembling something I would draw (or construct out of LEGO) as a kid, each railcar had an attached piece of track with ramps so that as the other car approached it, it would ride up onto this piece of track and travel over the top. Once the car reached the end of the track, it would change direction and allow passengers in the other car to experience what they had just been through.

Of course, back then, safety standards were a far cry from what they are today, and like many of the other attractions at Coney Island during its heyday, it had questionable safety qualities, and although people were not as likely to sue as they would today, this ride was allegedly shut down because of these questionable safety qualities. Dreamland itself closed several years later in 1911 having suffered the same fate as many Coney Island attractions of the time – it completely burned to the ground. Today the New York Aquarium sits on the site. Luna Park also partially burned down, but much later, in 1944, when it too closed.

Could this technology have been developed further, assuming they could work out the safety concerns? Personally, I do not think this would be likely, for multiple reasons. One of course is the maintenance issues associated with such a system and the complexity of implementing it on anything other than straight track. Speed would also be an issue – some trains today can go at several hundreds of kilometers an hour (at least in some parts of the world), and implementing such a system at high speeds would require extremely long “ramps” on each rail vehicle to avoid sudden jerking forces on the passengers (plus luggage, food, and anything else on board) as it traverses what is essentially a giant speed bump. Along with the increased height of the stacked vehicles, having the extra rails in the center of the vehicle also meant that the passenger compartments were located at the sides of the vehicle, requiring a much larger loading gauge, both laterally and vertically. Today with modern signalling and warning systems, as well as radio communication, rail collisions are very unlikely, and most collisions between two trains are often the result of human error, just as a car crash can be caused by a motorist running a red light.